DRIVE-IN CINEMAS: The Past and The Future of Cinema

In the age of social distancing, we expect it is time to bring something from the past: drive-in cinemas. Why not? it’ll be the safest and most comfortable way of getting resolute see a movie. A drive-in cinema consists of an outsized outdoor movie screen, projection booth, concession stand, and an outsized lot of vehicles. The enclosed area allows customers to look at movies from the protection, privacy, and luxury of their cars.

A short history of drive-in cinemas

Early drive-in cinemas

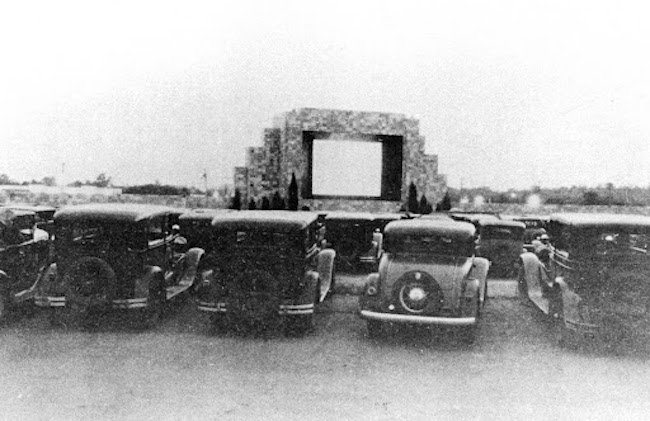

New Mexico opened a partial drive-in theater called Theatre de Guadalupe in town on April 23, 1915. Bags of Gold, under Siegmund Lubin’s production, became the first-ever movie they showed there. Later renamed De Lux Theatre, they closed down in July 1916.

In 1921, Claude V. Caver opened a drive-in cinema in Comanche, Texas. He obtained a permit from the town government to project films downtown. With cars parked bumper-to-bumper, Caver let patrons witness the screening of silent films from their vehicles. During this point, outdoor movies became a preferred summer entertainment activity.

The first-ever patented drive-in theater

Chemical company magnate Richard M. Hollingshead, Jr. patented the drive-in theater in Camden, New Jersey. In 1932, he conducted outdoor theater tests in his driveway at 212 Thomas Avenue in Riverton. He nailed a screen to trees in his backyard and founded a 1928 Kodak projector on the hood of his car. He, then, put a radio behind the screen testing the various sound levels along with his car windows down and up.

Hollingshead applied for a patent of his invention on August 6, 1932, where the govt. gave him the U.S. Patent 1,909,537 on May 16, 1933. He, then, opened his drive-in cinema in New Jersey on June 6, 1933, on Admiral Wilson Boulevard in Pennsauken Township near the Cooper River Park. It offered 400 slots and a 40 x 50 feet screen. He also advertised with a slogan, “The whole family is welcome, irrespective of how noisy the kids are.”

The peak of drive-in cinema

As car ownership, suburban and rural population rises in 1945, it led to a boom in drive-in cinemas with hundred being opened annually. This resulted in the baby-boom generation, and more cars being purchased as wartime fuel rationing ends. In 1947, Americans saw 155 openings of drive-in cinemas which rose to 4,151 by 1951.

The peak of drive-in cinemas came within the late 1950s and early 1960s, particularly in rural areas. It became a less expensive alternative to indoor cinema theaters. Not only did it saved the gas of driving out, visiting the town, and back home. But, it also saved in building and maintaining the drive-in cinema.

The fall of drive-in cinemas

Drive-ins catered to their known audience. They offered luxuries like bottle warmers, diaper vending machines, and later golf game courses, swimming pools, and even motels. During the 1950s, the greater privacy offered to patrons gave drive-ins a reputation as immoral. Then, they were labeled as “passion pits” within the media.

Beginning within the late 1960s, the attendance in drive-in cinemas began to say no because of the results of improvements and changes to home entertainment. the increase of color TV to cabled TV, VCRs, and video rental pushed drive-in cinemas away. Lower use of automobiles also made it increasingly difficult for drive-in theaters to stay profitable.

Perfect for a post-coronavirus world

A solution to entertainment in an exceedingly time of social distancing

With the coronavirus disease (COVID-19) continuing to become a danger to society, people remained wary and careful. They observe social distancing as much as they can. People are getting restless. Unfortunately, they can’t just go out and watch a movie due to the lockdowns and closures that indoor theaters experience.

Drive-in cinemas might become the new normal in the post-coronavirus world. With that said, drive-in theater owners still need to make sure that they maintain social distancing and follow basic health regulations. They might need to check employees’ temperature, wearing masks and gloves, and lower their customer capacity to stay them a minimum of six feet apart.

Read more articles from Village Pipol here.

Angela Grace P. Baltan has been writing professionally since 2017. She doesn’t hesitate to be opinionated in analyzing movies and television series. Aside from that, she has an affinity for writing anything under the sun. As a writer, she uses her articles to advocate for feminism, gender equality, the LGBTQIA+ community, and mental health among others.